- The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States

- We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

About this Article

- Part 1: Other uses of the term

- Part 2: Debates in Convention, the First drafts

- Part 3: Debates in Convention, Committee of Detail

- Part 4: Final Drafts and Debates of the Convention

- Part 5: Final thoughts on the Constitution Convention

- Part 6: The Anti-Federalist concern, limitless power

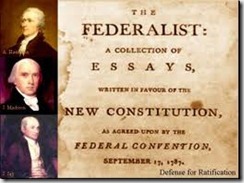

- Part 7: The Federalist presentation

- Part 8: The States Debates during Ratification (States 1-6)

- Part 9: State Ratification Debates (States 7-14)

- Part 10: Post Ratification Writings

- Part 11: Final Thoughts

Other Uses of General Welfare

Perhaps the first place to look is the immediate predecessor to the Constitution, the Articles of Confederation. Two times the term “General Welfare” appears in the Articles.

Perhaps the first place to look is the immediate predecessor to the Constitution, the Articles of Confederation. Two times the term “General Welfare” appears in the Articles.- The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever.

- All charges of war, and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense or general welfare, and allowed by the United States in Congress assembled, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury, which shall be supplied by the several States in proportion to the value of all land within each State, granted or surveyed for any person, as such land and the buildings and improvements thereon shall be estimated according to such mode as the United States in Congress assembled, shall from time to time direct and appoint.

- We, the representatives of the freemen of Pennsylvania, in general convention met, for the express purpose of framing such a government, confessing the goodness of the great Governor of the universe (who alone knows to what degree of earthly happiness mankind may attain, by perfecting the arts of government) in permitting the people of this State, by common consent, and without violence, deliberately to form for themselves such just rules as they shall think best, for governing their future society, and being fully convinced, that it is our indispensable duty to establish such original principles of government, as will best promote the general happiness of the people of this State, and their posterity, and provide for future improvements, without partiality for, or prejudice against any particular class, sect, or denomination of men whatever, do, by virtue of the authority vested in use by our constituents, ordain, declare, and establish, the following Declaration of Rights and Frame of Government, to be the CONSTITUTION of this commonwealth, and to remain in force therein for ever, unaltered, except in such articles as shall hereafter on experience be found to require improvement, and which shall by the same authority of the people, fairly delegated as this frame of government directs, be amended or improved for the more effectual obtaining and securing the great end and design of all government, herein before mentioned.

- That all government of right Originates from the people, is founded in compact only, and instituted solely for the good of the whole.

New York (April 20, 1777), and North Carolina (December 18, 1776) contain a similar use in their respective preambles.

New York (April 20, 1777), and North Carolina (December 18, 1776) contain a similar use in their respective preambles.- New York, “…institute and establish such a government as they shall deem best calculated to secure the rights and liberties of the good of the people of this state, most conducive of the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular, and America in General”.

- North Carolina, “…for the express purpose and framing a Constitution, under the authority of the people, most conducive to their happiness and prosperity, do declare, that a government of this State shall be established…”.

- New Hampshire [P2A5] And farther, full power and authority are hereby given and granted to the said general court, from time to time, to make, ordain, and establish, all manner of wholesome and reasonable orders, laws, statutes, ordinances, directions, and instructions, either with penalties, or without, so as the same be not repugnant or contrary to this constitution, as they may judge for the benefit and welfare of this state, and for the governing and ordering thereof, and of the subjects of the same, for the necessary support and defense of the government thereof, and to name and settle biennially, or provide by fixed laws for the naming and settling

Of all the instances we see “General Welfare” or some similar term in a charter of Government prior to the Constitution, only two of them occurred in a section that delegated a function of power. In regard to one in the Articles of Confederation, it is apparent it did not give the Congress Assembled [the proper term of Congress under the Articles] the reign of power as general welfare is contended to give today. The Articles proved to be ineffective in governance of a Nation due to the lack of power it had. In conjunction with general welfare in the Articles, we also see the similar phrase “Common Defense” preceding it as we do in the current Constitution, yet with both of these powers, the Articles lacked the ability to quell a rebellion in Massachusetts. If the term was to convey the power it is argued it does today, the Congress Assembled would have had the power to not only deal with this rebellion as it concerned the General Welfare of the whole nation, it would also have provided for the common defense from armed insurrection, yet IT DID NOT. general Welfare in the Articles conveyed no power to the Congress Assembled, because it was not meant to, it was used only as a general term describing the following enumerated powers that were granted to the Congress Assembled, none of which included the ability to confront rebellion or insurrection. It can only reason, that this term was in fact not a power delegating clause in the Articles of Confederation, and can only be nothing more than a descriptive term of the general purpose, not responsibility, of the government.

Of all the instances we see “General Welfare” or some similar term in a charter of Government prior to the Constitution, only two of them occurred in a section that delegated a function of power. In regard to one in the Articles of Confederation, it is apparent it did not give the Congress Assembled [the proper term of Congress under the Articles] the reign of power as general welfare is contended to give today. The Articles proved to be ineffective in governance of a Nation due to the lack of power it had. In conjunction with general welfare in the Articles, we also see the similar phrase “Common Defense” preceding it as we do in the current Constitution, yet with both of these powers, the Articles lacked the ability to quell a rebellion in Massachusetts. If the term was to convey the power it is argued it does today, the Congress Assembled would have had the power to not only deal with this rebellion as it concerned the General Welfare of the whole nation, it would also have provided for the common defense from armed insurrection, yet IT DID NOT. general Welfare in the Articles conveyed no power to the Congress Assembled, because it was not meant to, it was used only as a general term describing the following enumerated powers that were granted to the Congress Assembled, none of which included the ability to confront rebellion or insurrection. It can only reason, that this term was in fact not a power delegating clause in the Articles of Confederation, and can only be nothing more than a descriptive term of the general purpose, not responsibility, of the government.Debates in Convention, the First Drafts

The term General Welfare came up very early in the Convention, the first day after the rules of the Convention had been agreed upon, we see its first use. On May 29, 1787 Edmund Randolph, he Governor of Virginia rose and presented a proposed outline to a new Constitution, known commonly today as the Virginia Plan. In the very first resolution, Randolph he state the purpose of his proposal.

-

1. Resolved that the Articles of Confederation ought to be so corrected & enlarged as to accomplish the objects proposed by their institution; namely, "common defence, security of liberty and general welfare” 1

On May 30th, the Convention broke to committee to consider Randolph’s resolutions, with his first resolution postponed indefinitely, in order to consider the following.

-

That a union of the states merely federal will not accomplish the objects proposed by the Articles of Confederation—namely, common defence, security of liberty, and general welfare. 1

This resolution was in addition to two others agreed to regarding the general concepts of forbidding the States from making treaties, and making a government consisting of three branches, Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary. The use of the term here has no differing meaning than what Randolph had proposed the prior day in the Virginia Plan.

June 13th is the next time we encounter either general welfare itself, a draft of what would be the final version of Article I Section 8 Clause 1 or comparable scope of power, on a report from committee concerning a the basic structure of a new government [prelude to the New Jersey Plan].

- 6. Resolved, That the national legislature ought to be empowered to enjoy the legislative rights vested in Congress by the Confederation; and moreover, to legislate in all cases to which the separate states are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation; to negative all laws passed by the several states contravening, in the opinion of the national legislature, the Articles of Union or any treaties subsisting under the authority of the Union. 1

On June 15th the new Jersey Plan was submitted by William Patterson [New Jersey], with the 3rd Resolution addressing the ability to tax, in proportion to the population of all free persons, and indentured servants [excluding Indians not taxed]. But no mention of the purpose of the power to tax is described as we would come to see it in the Constitution.

The debates of the New Jersey plan carry into June 16th, when James Wilson [Pennsylvania] brought up 13 points in regards to the New Jersey Plan. His 6th point was:

-

6. The national legislature is to make laws in all cases to which the separate states are incompetent, &c.; in place of this, Congress are to have additional power in a few cases only. 1

James Wilson later on, while discussing the necessity to divide the Legislature into two house, made the following point in regards to Congress in a single Legislature:

-

If the Legislative Authority be not restrained there can be neither liberty nor stability. 1

Though this resolution does directly reflect either general welfare or its clause, it does go toward showing the desire of the convention to base the power structure off of the Articles of Confederation, and expand them as needed.

It was not until July 17th that General Welfare was again discussed [in the records of the notes whom attended and the Federal Journal].

-

Mr. [Roger] SHERMAN observed, that it would be difficult to draw the line between the powers of the general legislature and those to be left with the states; that he did not like the definition contained in the resolution; and proposed, in its place, to the words “individual legislation,” inclusive, to insert “to make laws binding on the people of the United States in all cases which may concern the common interests of the Union; but not to interfere with the government of the individual states in any matters of internal police which respect the government of such states only, and wherein the general welfare of the United States is not concerned.” 1

Roger Sherman [Connecticut] was discussing the following clause from the day before.

-

“And moreover to legislate in all cases to which the separate states are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation,” 1

Back to Roger Sherman’s motion, after being opposed by Gouverneur Morris [Pennsylvania] that some items the States did need policing, such as paper money, Roger Sherman defended the proposal by.

-

“in explanation of his idea, read an enumeration of powers, including the power of levying taxes on trade, but not the power of direct taxation.”. [italics noted in Madison’s Notes on the convention] 1

In the end Roger Sherman’s proposal failed by a substantial 8-2 vote. But what is to note here is, nowhere in the discussion was General Welfare moved to be a power of General Power, but was rather simply used as a passive term of description of the purpose of his proposal. The debate centered around how to effectively divide National from State powers, and the overall premise was the National government could not interfere with the actions of a State, unless it was against the interest of the “general welfare”, of the United states as a whole. as he later explained was limited to the enumerated powers and levying of taxes on trade. In the whole context, the idea was not to enable the National government to do things it felt were in the National welfare, but to prevent only those that were actions by states that were against the whole National welfare. As it was implied in this instance, it was not making reference to it is a general enabling power to a governing body.

The fact that the “incompetent’ drew a significant amount of attention from several delegates due to its potential of allowing the government to expand its powers to those it was not intended, while the term “general welfare” was drew no objections at all, goes to only supports the previous notion, that this term is used as a general meaning phrase to describe purpose and not a power enabling general clause. The whole debate around this single use is substantial in that it also was in reference of taxing power, the power that would eventual be described in the very same clause general welfare ended up in.

On July 26th resolutions were agreed to on the basic structure of the new Constitution, included in these is Resolution 6:

- 6. Resolved, That the national legislature ought to possess the legislative rights vested in Congress by the Confederation; and, moreover, to legislate in all cases for the general interests of the Union, and also in those to which the states are separately incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation.

- Art VI – The Legislature of the United states shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, imposts, and excises. 2

Similar to the Articles of Confederation, and the same as we see in the final Constitution, Charles Pinckney [who also did sign the Constitution] follows these up with enumerated powers clauses, 20 to be exact, as well as another set of prohibitive clauses, all very near what we see in the present Constitution, including direct taxes proportioned to the number of free inhabitants, before being allowed to be done in a manner as Congress directs [lest Capitation taxes which are to remain proportional]. But nowhere in Pinckney’s proposal is any sort of general welfare or general power to Congress mentioned or implied.

Through July 26th, General Welfare or any form of it, has been used very sparingly and sporadically, and thus far used mainly in reference to the use of it in the Articles of Confederation. But debates have already taken place about other aspects of Congressional power and is it being restrained enough, but not one of these was on the term general welfare. Up to this point in the Convention it does not seem to appear that general welfare is anything more than the term that was used in the Articles of Confederation which carried no weight of power at all, because why would they debate ‘incompetence’ as being too much power to Congress and draw the ire of at least half the delegates based on the split vote for its removal, but not even mention once an opposition “general welfare” also as being a power that may give Congress too much power?

Debates in Convention, Committee of Detail

-

That the Legislature of the United States ought to possess the legislative Rights vested in Congress by the Confederation; and moreover to legislate in all Cases for the general Interests of the Union, and in those Cases to which the States are separately incompetent, or in which the Harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the Exercise of individual Legislation.

In regards to the general Interests of the Union, does not appear specific to either a broad or relegated power, but rather simply referring to matters which affect the Union as a whole. As for Harmony of the United States, the roughness of the concepts is apparent since this concept does not appear in the final draft of the constitution and changes along the way in debates, even so the intention of it is clear for this clause, to give the Congress the power to negative State laws which are contrary to the general harmony of the union. Though no example is given it appears the intent of this clause is to prevent states from enacting laws which may be detrimental to one or more other states, or the relationship of the United States as a whole to foreign states.

The second draft in the Committee of Detail is much more of an outline than the first draft, though some powers of Congress are specified such as a Council of Revision appealing disputes between states, most are not what we would be familiar with today, and no mention of any type of general power is included in them. The second draft does contain a generic preamble.

-

A Confederation between the free and independent States of N. H. &c. is hereby solemnly made uniting them together under one general superintending Government for their common Benefit and for their Defense and Security against all Designs and Leagues that may be injurious to their Interests and against all Forc[e] and Attacks offered to or made upon them or any of them

As with other preamble, this describes the purpose of the document. In it the term common Benefit is used, which is strikingly different from general welfare. Common Benefit or Common Advantage is clearly used in regards to the National [Superintendent] Government exercising powers that benefit or give an advantage to all, and for their defense against foreign states. This differs from general welfare in that general welfare does not itself imply it must be for the benefit of all or even most, but rather for the nation in general while it may not be for the benefit or advantage of the some. But since this is also part of the preamble, and does not exist in a power enabling clause, this is used as purely a descriptive term for what the objective of the government is to do, and not to imply a power.

Of the powers in the second draft that are delegated one of note deserves attention in regards to general welfare.

-

10. Each State retains its Rights not expressly delegated — But no Bill of the Legislature of any State shall become a law till it shall have been laid before S. &. H. D. in C. assembled and received their Approbation.

Here the express rights of powers not specifically delegated to the Congress, are clearly reserved to the states. That being it strongly limits to what congress can do in specific terms, and does not leave in doubt what Congress does and does not possess. It also requires that all Legislation from the States must receive the assent of Congress prior it to be enacted into law. This hails back to the first draft in which “the Harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the Exercise of individual Legislation”, was included in the powers to the legislature. Here with this clause we see that concept developed as to how it is to be done, as we also see the powers of Congress being developed from the rough first draft to here, though far from complete and in mainly context only.

The third draft of the Constitution the discussion of a preamble occurs, and more specific enumerated and prohibitive powers to the Legislature are addressed. For the preamble, it is discussed that a preamble should be part of the Constitution, but it should only be written after the final draft is completed first. The discussion does states that the preamble should

-

But the object of our preamble ought to be briefly to (represent) declare, that the present foederal government is insufficient to the general happiness, that the conviction of this fact gave birth to this convention

The third draft also includes much more detailed powers and restrictions of the Legislature. This is broken into three parts, under the title “The Legislative”. Part 1 is the legislative powers (with exclusions and restriction), Part 2 is Certain Exception, and Part 3 is Certain Restriction. [Note this is the transcript from Wilson’s Notes, it is not a formatting error]

Part 1

-

1. To raise money by taxation, unlimited as to sum, for the (future) past (or) 〈&〉 future debts and necessities of the union and to establish rules for collection

-

No Taxes on exports. —

Restrictions

-

1. direct taxation proportioned to representation

-

2. No (headpost) capitation-tax which does not apply to all inhabitants under the above limitation (& to be levied uniform)

-

3. no (other) indirect tax which is not common to all

-

4. (Delinquencies shall be be distress — [illegible words])

-

4. To regulate commerce 〈both foreign & domestic〉

-

2. 〈no State to lay a duty on imports —〉

Part 1 of above states what the Legislature may do, here in regards it may raise money and how it may spend it, [as well as prohibiting states from Taxing imports in section 2]. This is followed by Exceptions of what it may not tax under any circumstance, than by restriction certain manner that taxes may only be applied in certain aspects. Also contained in Part 1 is the manner in which tax revenue may be used, to pay for past and future debts and necessities of the union. The necessities of the union may be extensive and does not include a limiting factor in the clause. But following Part 1, Part 2 and 3 is a list exceptions and restriction, of what the Legislature may not do, when excursing its power in Part 1.

2. Exceptions

-

1. no Duty on exports.

-

2. no prohibition on (such) 〈ye〉 Importations of 〈such〉 inhabitants 〈or People as the sevl. States think proper to admit〉

-

3. no duties by way of such prohibition.

Only regulating commerce and the importation of inhabitants [Slaves] the restrictive and exclusive clauses have been in regards to Taxing and duties, though both commerce and importation of slaves would fall under these notions in some respect. To this point no restriction or exceptions have been addressed as in how it may or not be applied to debts and necessities of the union. Part 3 does just this, it list what restrictions the Legislature has on it in regards to making laws [accumulating debts].

3 Restrictions

-

1. A navigation act shall not be passed, but with the consent of (eleven states in) 〈⅔d. of the Members present of〉 the senate and (10 in) 〈the like No. of〉 the house of representatives.

-

(2. Nor shall any other regulation — and this rule shall prevail, whensoever the subject shall occur in any act.)

-

(3. the lawful territory To make treaties of commerce (qu: as to senate)[ ] Under the foregoing restrictions)

-

4. (To make treaties of peace or alliance(qu: as to senate)NA under the foregoing restrictions, and without the surrender of territory for an equivalent,and in no case, unless a superior title.)

-

5. To make war〈: (and)〉 raise armies. 〈& equip Fleets.〉

-

6. To provide tribunals and punishment for mere offences against the law of nations.〈Indian Affairs〉

-

7. To declare the law of piracy, felonies and captures on the high seas, and captures on land.〈to regulate Weights & Measures〉

-

8. To appoint tribunals, inferior to the supreme judiciary.

-

9. To adjust upon the plan heretofore used all disputes between the States 〈respecting Territory & Jurisdn〉

-

10. To (regulate) 〈The exclusive right of〉 coining 〈money (Paper prohibit) no State to be perd. in future to emit Paper Bills of Credit witht. the App: of the Natl. Legisle nor to make any (Article) Thing but Specie a Tender in paymt of debts〉

-

11. To regulate naturalization

-

12. (To draw forth the) 〈make Laws for calling forth the Aid of the〉 militia, (or any part, or to authorize the Executiveto embody them) 〈to execute the Laws of the Unionto repel Invasion to inforce Treaties suppress internal Comns.〉

-

13. To establish post-offices

-

14. To subdue a rebellion in any particular state, on the application of the legislature thereof.〈of declaring the Crime & Punishmt of Counterfeitg it〉

-

15. To enact articles of war.

-

16. To regulate the force permitted to be kept in each state.

-

(17. To send embassadors)〈Power to borrow Money-To appoint a Treasurer by (joint) ballot.〉

-

18. To declare it to be treason to levy war against or adhere to the enemies of the U. S.

-

19. (To organize the government in those things, which)

The fourth draft from the Committee contains two separate sections regarding the powers of Congress. The first is under the section labeled “An Appeal for the Correction of all Errors both in Law and Fact”. But this first part appears to be the first draft of correction, since it differs from the second in the same draft.

-

That the United States in Congress be authorised — to pass Acts for raising a Revenue, — by levying Duties on all Goods and Merchandise of foreign Growth or Manufacture imported into any Part of the United States — by Stamps on Paper Vellum or Parchment — and by a Postage on all Letters and Packages passing through the general Post-Office, to be applied to such foederal Purposes as they shall deem proper and expedient — to make Rules and Regulations for the Collection thereof — to pass Acts for the Regulation of Trade and Commerce as well with foreign Nations as with each other to lay and collect Taxes

What the Congress “shall deem proper and expedient” in regards to the application of revenues raised by the various methods mentioned appears to infer Congress with substantial power in the manner of making law. But since this under the “Correction of Errors” portion, is this addressing what changes are desired to be made from or changes to? Since many of these provisions are not expressed in previous drafts it appears that the desire is to change to these provisions.

Also included is an enumerated powers section as seen in draft three.

-

The Legislature of U. S. shall have the exclusive Power — of raising a military Land Force — of equiping a Navy — of rating and causing public Taxes to be levied — of regulating the Trade of the several States as well with foreign Nations as with each other — of levying Duties upon Imports and Exports — of establishing Post-Offices, and raising a Revenue from them — of regulating Indian Affairs — of coining Money — fixing the Standard of Weights and Measures — of determining in what Species of Money the public Treasury shall be supplied.

Here powers are enumerated similar to what was seen in draft three, the difference with these enumerated powers is the statement “The Legislature of the U.S. shall have exclusive Power”. It is not limiting power strictly to these provisions included, but rather it is granting Congress the sole power to make law on these provisions. Here we see the intention or at the very least the ability of the Legislature to have a more broad scope of power than is seen in any previous version, that is not well defined to limit, but instead gives exclusive power with few limits.

In the final draft from the Committee of Detail the one presented to the Convention as a whole on August 6th is draft five. This is the refined draft it includes a preamble and also enumerated and prohibitive powers to the Congress. In the preamble, it is simple stating the states ordain, declare and establish this Constitution for themselves and posterity.

The powers and restriction on Congress are in Article 8.

-

The Legislature of the United States shall have the (Right and) Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises; to regulate (Naturalization and) Commerce 〈with foreign Nations & amongst the several States〉; to establish an uniform Rule for Naturalization throughout the United States; to coin Money; to regulate the (Alloy and) Value of 〈foreign〉 Coin; to fix the Standard of Weights and Measures; to establish Post-offices; to borrow Money, and emit Bills on the Credit of the United States; to appoint a Treasurer by Ballott; to constitute Tribunals inferior to the Supreme (national) Court; to make Rules concerning Captures on Land or Water; to declare the Law and Punishment of Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and the Punishment of counterfeiting the 〈Coin〉 (and) 〈of the U. S. &〉 of Offences against the Law of Nations; (to declare what shall be Treason against the United States;) 〈& of Treason agst the U: S: or any of them; not to work Corruption of Blood or Forfeit except during the Life of the Party;〉 to regulate the Discipline of the Militia of the several States; to subdue a Rebellion in any State, on the Application of its Legislature; to make War; to raise Armies; to build and equip Fleets, to (make laws for) call(ing) forth the Aid of the Militia, in order to execute the Laws of the Union, (to) enforce Treaties, (to) suppress Insurrections, and repel invasions; and to make all Laws that shall be necessary and proper for carrying into (full and complete) Execution (the foregoing Powers, and) all other powers vested, by this Constitution, in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof; (sic)

The powers listed here are defined as “the Legislature of the United States shall have the (Right and Power to…”. This is stating what specific rights they have been granted in legislating. Nowhere in the final draft from the Committee of Detail does general welfare or any similar term appear. The powers of Congress are defined stated clearly, with no broad or general term included.

Much debate lies ahead with what the Committee of Detail will present, with many changes still to take place before the Constitution is to be finished. But as the Committee of Details submits its draft for a Constitution, it does not contain General welfare, and similar phrase nor does it grant Congress in any manner a broad scope of powers..

To this point in the Convention still the only references to general welfare or similar phrases have been in reference to or from the Articles of Confederation, or used in a similar if not the same manner as used in the Articles of Confederation, which as previously discussed conveyed no power specifically to the Congress Assembled. Rather it was used as a descriptive term, not a power enabling term, and to this point, only one instance of giving the Congress a broad scope of power in draft has been seen, in the correction of errors section of draft four in the Committee of Detail, which in the subsequent part of the draft had been removed, and did not appear in the final draft from the committee. As it stands, general welfare is not included in the current draft going back to the full convention, and to this point in the convention, is only a descriptive term, and not a power giving one.

Final Drafts and Debates of the Convention

Article VII Section Clause 1 reads:

-

The legislature of the United States shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises.

Just as with the following 17 clauses after this clause, general welfare or any similar variant does not appear anywhere within these 18 clauses.

It would not be until the next day a reference to General welfare in some would appear, but it would be tied to Article III of the proposed Constitution. Article III concerned establishing the Legislature to consist of two bodies, each having a negative on the other [not giving assent to the others bills], and when it should meet.

-

Art. III.—The legislative power shall be vested in a Congress, to consist of two separate and distinct bodies of men, a House of Representatives and a Senate; each of which shall in all cases have a negative on the other. The legislature shall meet on the first Monday in December in every year.

The question arose when George Mason [Virginia] proposed to substitute “legislative acts'” for “all cases” in Article III. At this point in the Convention, the notion of the President being selected by the National Legislature was still the what was being used. In response to the substituting strictly legislative acts instead of all cases, Nathaniel Gorham [Massachusetts] contended the election of the President should be by joint ballot, with “The only objection against a joint ballot is, that it may deprive the Senate of their due weight; but this ought not to prevail over the respect due to the public tranquillity and welfare.” This use of a term similar to General Welfare is neither descriptive, or power enabling in any manner, but is a general statement to the overall political welfare of the nation, since it was in direct correlation with the selection of the President and ensuring a firm manner of doing so. It is also to note, that this motion did ultimately fail to carry.

Later in the Day George Read [Delaware] proposed to add, “subject to the negative to be hereafter provided” [to give the president an absolute negative/veto on legislation], He considered this essential to the preservation of Liberty and to “the public welfare”. But as earlier, this term is used as a general descriptive term, not in a power enabling manner, but in a manner from which another source of power is described specifically and this term be used to describe one of its attributes that of the Public welfare. This motion also failed to carry, since the concept of an absolute Executive negative had been virtually settled earlier in the Convention.

Over the next several days the proposed enumerated and prohibitive powers were debated, with some drawing more attention than others in debate and proposed changes to them. But at no time during these debates was a general power discussed or agreed to by the Convention. The closest the Convention came to in regards to general welfare may be the debate and subsequent agreement in the new Federal Government assuming the foreign debts of the states upon ratification.

The next instance of a general power or in this case a controlling power of the people occurs on August 20th. George Mason moved to enable Congress “to enact sumptuary laws”. [law designed to restrict excessive personal expenditures in the interest of preventing extravagance and luxury 3]. This was countered by Oliver Ellsworth [Connecticut] “The best remedy is to enforce taxes and debts. as far as the regulation of eating and drinking can be reasonable, it is provided for in the power of taxation”. This clause was soundly defeated shortly afterwards, and does not contain general welfare or a similar meaning. But it is worth noting the broad acceptance of taxation as presented by Ellsworth, that taxation could enact just such a thing. But it should also be noted it was only taxation that was addressed in the clause, not another term and that general welfare had yet to be added to the taxation clause, and that Gouvernuer Morris [Pennsylvania] argued against the notion of sumptuary laws prior to its quick defeat in the Convention.

On August 21st, William Livingston [New Jersey] reported to the Convention from the committee of Eleven [made for the purpose of refining the Constitution] a clause regarding the Legislature.

-

The legislature of the United States shall have power to fulfil the engagements which have been entered into by Congress, and to discharge, as well the debts of the United States, as the debts incurred by the several states, during the late war, for the common defence and general welfare.

This provision mainly deals with what will become Article VI in the assumption of the debts and contracts of the United States. The clause states a couple different things, that the United States will honor the contracts [engagements] prior to this Constitution, and that the debts incurred by the States and the United States during the late war [The American Revolution] for the common defense and general welfare will also be honored. As we have seen in previous instances, common defense and general welfare appear together, and as before are descriptive terms and do not convey power. The use of general welfare here can only be descriptive since it is referring to a past instance. The clause clearly states the debts of the United States and States during the late war. Well war for all intent is for the common defense and general welfare [to protect liberty, lives and property], so common defense and general welfare are simply describing what the past debts of the war were made for. As previously discussed, general welfare under the Articles of Confederation [which the United States was operating under at the end of the war] did not in themselves convey any power with its use of the term general welfare. Here is another instance of general welfare being strictly a descriptive term in regards to another subject already present [war in this instance], and not a standalone phrase or clause on its own accord.

-

‘for payment of the debts and necessary expenses of the United States; provided that no law for raising any branch of revenue, except what may be specially appropriated for the payment of interest on debts or loans, shall continue in force for more than—years.

The taxation clause changes recommended by the Committee of Eleven include no mention of general welfare, and the original version did not include it either. The second instance came later on in regards to Article VII, Section 2 Clause 16 [Note 1]

-

and to provide, as may become necessary from time to time, for the well managing and securing the common property and general interests and welfare of the United States in such manner as shall not interfere with the government of individual states, in matters which respect only their internal police, or for which their individual authority may be competent.

Since the exact Clause this is is meant to change, it is more difficult to determine what the exact purpose of the addition, but appears most likely to be article VII, Section 1 Clause 17. But from what is written, it can be seen that general welfare and interest are used in a common descriptive manner. Common Property is used in conjunction with general interest and welfare, and is than tempered with an interference section with the states, and requiring it to be with respect with policing which the state is competent. This is to say in conjunction with the state, but on a not to interfere basis. So even if this use of general interest and welfare is more broad and power enabling, it is immediately restricted to when, where and how it may be used, and only to secure the common property and general interest and welfare. At the least this use of general interest and welfare is a descriptive term to what may be secured, at the most it is a broad term to what may be secured, but is also accordingly restricted to a defined narrow use.

This use of general interest and welfare is not being recorded as approved or declined, but it was probably defeated since it does not appear anywhere else in the records of the Convention.

On August 22 Article VII Section1 was amended and agreed to.

- “The legislature shall fulfil the engagements and discharge the debts of the United States; and shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises;”

This is a combination of what would become Article I Section Clause 1 and Article VI. But of note, it is agreed to on August 22 does not contain general welfare.

It would not be until September 12 that even so much as welfare again appears in the records of the convention, when William Johnson [Connecticut] submits a draft of the Constitution to the Convention. In the final paragraph of his letter to the Convention he states:

-

“That it will meet the full and entire approbation of every state is not, perhaps, to be expected. But each will doubtless consider, that, had her interest alone been consulted, the consequences might have been particularly disagreeable and injurious to others. That it is liable to as few exceptions as could reasonably have been expected, we hope and believe; that it may promote the lasting welfare of that country so dear to us all, and secure her freedom and happiness, is our most ardent wish.”

The last time general welfare is used in the Convention prior to the agreement to the final draft is on September 14, three days before the Constitution would be signed. This in regards to Article I Section 8 [the same portion as it was in the final draft and we know it today].

Benjamin Franklin [Pennsylvania] proposed after “Post Roads” to include a power, “to provide for cutting canals where deemed necessary.” After James Wilson [Pennsylvania] seconded the motion, Roger Sherman [Connecticut] objected, due to it being an expense to the United States. James Wilson suggested it may be a source of revenue, to which James Madison [Virginia] suggested an enlargement of the motion into a power.

-

“to grant charters of incorporation where the interest of the United States might require, and the legislative provisions of individual states may be incompetent.”

The object was to secure easy communication between the states, free intercourse, the political obstacles had already been removed, this would remove the natural [geographic] obstacles. This was seconded by Edmund Randolph [Virginia]. Rufus King [Massachusetts] thought it unnecessary, while James Wilson countered with:

-

It is necessary to prevent a state from obstructing the general welfare.

After some more debate of on the lines of communication, and limiting the power to strictly canals for fear of monopolies implied by their construction, the motion and power failed to carry.

This was the final use of general welfare or any similar term in the Convention, until the final draft of the Constitution was signed on September 17th, and to this point it is still not part of Article I section 8, or the preamble.

Final thoughts on the Constitution Convention

But maybe the most telling non-debate of “General Welfare” was the total lack of it in the Slavery issue. As contended by some, general welfare was meant to give the Congress the power to make laws for the overall general welfare of the people or the Union. By using this clause by this meaning, would this not then give the power to Congress to outlaw Slavery or Indentured Service outright for the general welfare of those bound by it? But this possibility was never addressed once in the Convention by the accounts of the notes we have available to us today.

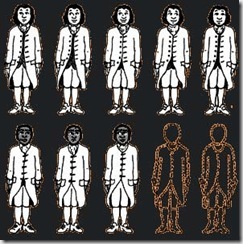

The three-fifths clause dealing with apportionment of Representatives to the States was debated off and on for over two weeks from the end of June until an agreement was finally passed on how non-freeman [Slaves] would be counted for both taxation and Representation. Without this compromise, it is doubtful the Constitution would have ever been ratified by the southern States, or even reach the Nine required to enact it at all. The southern States believed that they were the region of wealth, largely based off of their agricultural economy, but they also new they were outnumbered by a large amount in population by the Northern States [when counting only free men who could vote]. As pointed out on June 28th, “Virginia, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, have forty two ninetieths of the votes, they can do as they please, without a miraculous union of the other ten”.

Through the entire debate from the beginning of the Convention to the end general welfare was never attributed to the issue of Slavery. Their were proposals or suggestions to end the practice with the Constitution, or to enable it to be abolished Slavery with it, but also none of these ideas or suggestions were ever tied to general welfare as well. The issue of allowing slavery in the South for some was of enough importance, that a clause was added to Article I Section 9 prohibiting Congress from prohibiting the importation of Slaves, and in Article VII prohibiting an Amendment that would revoke it, or the apportionment of taxes using the Three-fifths measure. In the end of this issue after the 20 year provision had long passed, it took not an act of Congress to end slavery, but by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. With the amount of concern that was expressed on the power balance to the North, the fact that general welfare was never tied to this power balance, perhaps leads only to the support of it being a general statement and not invoking power at all.

When all things are considered on the Convention, almost every aspect in the Constitution and every aspect pertaining to power given to the Government was debated, and in most cases numerous times, except for the clause of “General Welfare and Common Defense”. Numerous sides to arguments existed in most provisions, some wanting stronger National Powers, others weaker, some looking out for states rights, other for the Individual. With all of these interest being represented to some degree, with almost every aspect of a power given to the Federal Government or power surrendered by the States or People being debated numerous times, to have general welfare inserted late in the Convention, and to never have even one debate on what General Welfare power is, is remarkable, unless it was viewed by all the Delegates in the Convention not as a power, but simply a description of something else, perhaps the following enumerated powers in Article I Section 8, just as general welfare did in the Articles of Confederation.

The Anti-Federalist concern, limitless power

Among some of the concerns addressed by the Anti-Federalist [there were many concerns among them] Article I Section 8 Clause 1 and general welfare was among them, and written about numerous times. Ironically, or perhaps prophetically the concerns addressed were generally that this clause and “general welfare”, was too great of a power, since it would be under only Congresses discretion to determine what was in the “general welfare” and this use would not only be used, but abused at the costs of the States and the people. What the Anti-Federalist show is the first real discussion of what the term may mean, and the power it may convey to the Congress.

The earliest time general welfare is seen in an Anti-Federalist writing is the Foreign Spectator on October 2, 1787. But has been mentioned before in Part 1, this use is general as to the purpose of the government, to ensure the “general welfare” or common good of the People, States and Nation. This was not used in a sense of power of government, but a descriptive term of the purpose of government. The same use is also found in Cato III (10-25-1787), Brutus V (12-13-1787), A Landlover VII (12-17-1787), Brutus XI (1-31-1788), Brutus XII (2-7-1788), Philadelphia XI (3-8-1788) and Fabious V (4-22-1788). Though a few of these references did address the preamble directly, the usage of the term is still used in a general manner as to purpose and not power. During some of the discussion some of the papers mention the ability of the Federal Government to either punish or compel States to abide by the treaties or such of the United States. This is defended by some Pro-Federalist writings in ensuring the “general welfare” of the United States (Such as A Citizen of Philadelphia in response to Brutus on 11-8-1787). Though A Citizen of Philadelphia, does respond using general welfare and it does discuss a power of Congress (or the Senate in this case in ratifying a treaty), the use is not in reference to Article I Section 8 Clause 1, but more or less a discussion into the supremacy of the Constitution according to Article VI. These instances will also not be discussed here, since they do not relate to general welfare as being discussed in this article, but do acknowledge there may be instances of “general welfare” being referred to a power given to the Federal Government, but that it is outside of this scope.

The first instance of concern over the clause itself occurs in A Federal Republican (Author Unknown) on November 28, 1787, ironically not a true Anti-Federalist, rather Pro-Federalist, but does address what will become common concerns.

-

Can any state, or the citizens of any state think themselves secure when they are conscious that their own laws will not avail them in competition with those of Congress? Suppose Congress in making its provision for the general welfare of the United States, and framing those laws which shall be deemed necessary and proper for carrying into execution all their powers, should, in the complex body of them, oppose the general system of state policy, what must be the consequence?

-

The legislature must have exclusive jurisdiction in all matters where the states have a mutual interest. There are some regulations in which all the states are equally concerned there are others which in their operations are limited to one state. The former belong to Congress, the latter to the respective legislatures. No one state has a right to supreme controul in any affair in which the other states have an interest; nor should Congress interfere in any affair which respects one state only.

However by leaving too much power in the hands of Congress, it may find ways to be oppressive upon the people or states through acts (Federal Republican speaks directly to taxation as such is the clause) in the name of “general welfare”.

-

Now, what can be more comprehensive than these words? Every species of taxation, whether external or internal are included. Whatever taxes, duties, and excises that the Congress may deem necessary to the general welfare may be imposed on the citizens of these states and levied by their officers. The congress are to be the absolute judges of the propriety of such taxes, in short they may construe every purpose for which the state legislatures now lay taxes, to be for the general welfare, they may seize upon every source of taxation, and thus make it impracticable for the states to have the smallest revenue, and if a state should presume to impose a tax or excise that would interfere with a federal tax or excise, congress may soon terminate the contention, by repealing the state law,…Indeed every law of the states may be controuled by this power. The legislative power granted for these sections is so unlimited in its nature, may be so comprehensive and boundless in its exercise, that this alone would be amply sufficient to carry the coup de grace to the state governments, to swallow them up in the grand vortex of general empire.

Centinel expounds on the concerns of Federal Republican, in the abuse on Congress in the power of taxation. Centinel speaks about how the Congress may use the power of taxation to starve the States of their ability to raise revenue by nullifying States laws. His concern is it may be a method to dissolve or render the State governments impotent and ineffective to have all authority resting solely under its umbrella. This thought is along the same lines of concern that Federal Republican, that the Congress is the sole power to decide what is in the “general welfare” and what is not. If Congress decides it is in the “general welfare” it would simply need to act upon it and have not consequence to the power structure it may be imposing on that of the States or the People.

-

Not only are these terms very comprehensive, and extend to a vast number of objects, but the power to lay and collect has great latitude; it [general welfare] will lead to the passing a vast number of laws, which may affect the personal rights of the citizens of the states, expose their property to fines and confiscation, and put their lives in jeopardy: it opens a door to the appointment of a swarm of revenue and excise officers to prey upon the honest and industrious part of the community, eat up their substance, and riot on the spoils of the country.

Brutus contends that this clause of general welfare, and coupled with necessary and proper, does not at all bind the Congress in what laws it may pass, since it is also the only body that is to judge what is for the “general welfare, and what is necessary and proper to execute it”.

-

It is truly incomprehensible. A case cannot be conceived of, which is not included in this power. It is well known that the subject of revenue is the most difficult and extensive in the science of government. It requires the greatest talents of a statesman, and the most numerous and exact provisions of the legislature. The command of the revenues of a state gives the command of every thing in it.-He that has the purse will have the sword, and they that have both, have every thing; so that the legislature having every source from which money can be drawn under their direction, with a right to make all laws necessary and proper for drawing forth all the resource of the country, would have, in fact, all power.

On December 12, 1787 Pennsylvania became the second state to ratify the Constitution after Delaware by a 2:1 vote if favor (46-23). But among those who voted Nay on the ratification present The Dissent of the Minority of the Pennsylvania Convention on December 18, 1787, addressing their concern on the Constitution. Among the concerns addressed by the minority dissent was general welfare. Just as Brutus was concerned about this power in regards to taxation and being combined with necessary and proper, so is the minority dissent in Pennsylvania. They are concerned this power may not leave an ability for the States to raise revenue and may be a means to abolish the State Governments or render them powerless.

-

As there is no one article of taxation reserved to the state governments, the Congress may monopolise every source of revenue, and thus indirectly demolish the state governments, for without funds they could not exist, the taxes, duties and excises imposed by Congress may be so high as to render it impracticable to levy further sums on the same articles;

-

The Congress might gloss over this conduct by construing every purpose for which the state legislatures now lay taxes, to be for the "general welfare," and therefore as of their jurisdiction. And the supremacy of the laws of the United States is established by article 6th, viz. "That this constitution and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby; any thing in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding." It has been alleged that the words "pursuant to the constitution," are a restriction upon the authority of Congress; but when it is considered that by other sections they are invested with every efficient power of government, and which may be exercised to the absolute destruction of the state governments, without any violation of even the forms of the constitution, this seeming restriction, as well as every other restriction in it, appears to us to be nugatory and delusive; and only introduced a blind upon the real nature of the government. In our opinion, "pursuant to the constitution," will be coextensive with the will and pleasure of Congress, which, indeed, will be the only limitation of their powers.

-

The new constitution, consistently with the plan consolidation, contains no reservation of the rights and privileges of the state governments, which was made in the confederation of the year 1778.

As a remedy to this specific issue, the minority proposed the following Amendment.

-

9. That no law shall be passed to restrain the legislatures of the several states from enacting laws for imposing taxes, except imposts and duties on goods imported or exported, and that no taxes, except imposts and duties upon goods imported and exported, and postage on letters shall be levied by the authority of Congress.

Brutus VI followed up from his previous article (Brutus V) on December 27, 1787. Brutus continues with those points, and contends that the power to raise revenue should reside mainly in the States and not at the whim of the Federal Government. He encourages measures to ensure this, that the Federal Government is limited in its ability to raise revenue and not allow general welfare be an open ended ability for the Federal Government to control issue that should be handled by the States instead. When he discussed what the limits of the power, he acknowledged that both sides were advocating for the “general welfare” but he follows up with a most interesting point.

-

It is as absurd to say, that the power of Congress is limited by these general expressions, "to provide for the common safety, and general welfare," as it would be to say, that it would be limited, had the constitution said they should have power to lay taxes, &c. at will and pleasure. Were this authority given, it might be said, that under it the legislature could not do injustice, or pursue any measures, but such as were calculated to promote the public good, and happiness.

The first point is he directly addresses general welfare as a “general expression”. Second he also refers to it in a meaning of purpose and generality, “promote the public good and happiness”. He nearly contends it to be a powerless statement, but does not go to that point. He still argues that this statement may render the ability of the states to raise revenue limited subject to the Congress, and the potential use of the power is too broad. In the end of the Article, similar to what the Pennsylvania Minority Dissent had done, Brutus recommends a means to ensure State power, in this case specifically in regards to revenue.

-

Upon the whole, I conceive, that there cannot be a clearer position than this, that the state governments ought to have an uncontroulable power to raise a revenue, adequate to the exigencies of their governments; and, I presume, no such power is left them by this constitution.

In Brutus VIII from January 10, 1788, Brutus once again addresses general welfare, in a portion in which he was discussing the power of the Congress to raise Armies as being indefinite and unlimited.

-

If the general legislature deem it for the general welfare to raise a body of troops, and they cannot be procured by voluntary enlistments, it seems evident, that it will be proper and necessary to effect it, that men be impressed from the militia to make up the deficiency.

Brutus is addressing the ability of Congress to be able to declare something [raising armies in this case] in the General Welfare, and accomplish it by means they are not directly empowered with. [Though on in this instance in particular, one could argue general welfare is not required for conscription and raising armies is sufficient]. But the relation Brutus is attempting to draw is how the power can be used for things OTHER than taxing if it is left unchecked.

-

These powers taken in connection, amount [to] this: that the general government have unlimited authority and controul over all the wealth and all the force of the union.

In Brutus XI from January 31, 1788 Brutus continues his attacks on the unlimited power that Congress may possess, in relation to general welfare as previously discussed among other concerns.

-

1st. The constitution itself strongly countenances such a mode of construction. Most of the articles in this system, which convey powers of any considerable importance, are conceived in general and indefinite terms, which are either equivocal, ambiguous, or which require long definitions to unfold the extent of their meaning. The two most important powers committed to any government, those of raising money, and of raising and keeping up troops, have already been considered, and shewn to be unlimitted by any thing but the discretion of the legislature. The clause which vests the power to pass all laws which are proper and necessary, to carry the powers given into execution, it has been shewn, leaves the legislature at liberty, to do every thing, which in their judgment is best. It is said, I know, that this clause confers no power on the legislature, which they would not have had without it-though I believe this is not the fact, yet, admitting it to be, it implies that the constitution is not to receive an explanation strictly, according to its letter; but more power is implied than is expressed. And this clause, if it is to be considered, as explanatory of the extent of the powers given, rather than giving a new power, is to be understood as declaring, that in construing any of the articles conveying power, the spirit, intent and design of the clause, should be attended to, as well as the words in their common acceptation.

And Brutus XII of February 2, 1788

-

This will certainly give the first clause in that article a construction which I confess I think the most natural and grammatical one, to authorise the Congress to do any thing which in their judgment will tend to provide for the general welfare, and this amounts to the same thing as general and unlimited powers of legislation in all cases.

Even though the Anti-Federalist did not prevent any state from ratifying, they caused delays in the ratification in some states, and close votes in others such as New York 30-27 (where the Federalist Papers were addressed to). The Anti-Federalist did succeed in exposing potential abuses of power, including “general welfare” in Article I. The exposure and contention of these potential abuses and lack of state power to stop it, or being delegated any power to it, did weigh heavily in the adoption of the Bill of rights, which included an amendment to prevent this abuse of power in regards to general welfare, the 10th Amendment.

The Federalist presentation

-

Some, who have not denied the necessity of the power of taxation, have grounded a very fierce attack against the Constitution, on the language in which it is defined. It has been urged and echoed, that the power "to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts, and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States," amounts to an unlimited commission to exercise every power which may be alleged to be necessary for the common defense or general welfare. No stronger proof could be given of the distress under which these writers labor for objections, than their stooping to such a misconstruction. Had no other enumeration or definition of the powers of the Congress been found in the Constitution, than the general expressions just cited, the authors of the objection might have had some color for it; though it would have been difficult to find a reason for so awkward a form of describing an authority to legislate in all possible cases. A power to destroy the freedom of the press, the trial by jury, or even to regulate the course of descents, or the forms of conveyances, must be very singularly expressed by the terms "to raise money for the general welfare."

-

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;

Madison also states earlier on, “Had no other enumeration or definition of the powers of the Congress been found in the Constitution, than the general expressions just cited, the authors of the objection might have had some color for it”. Here he is stating that specific powers are enumerated or defined, and the fact they are listed denies credence to the dissenting argument on the clause’s meaning. Madison is implying, why would such a broad power be put in place and then be followed by enumerated or defined powers which would by the opposing concept of general welfare[broad power] would be part of general welfare in the first place? The implication is, that general welfare is NOT a broad power, but is limited to taxing only, and the powers Congress does have are specifically enumerated and defined following clause 1. As was pointed out in Part 1, this same term used in a similar way conveyed no power to the Congress Assembled, and just such is summed up by Madison at the end of Federalist No 41.

-

The objection here is the more extraordinary, as it appears that the language used by the convention is a copy from the articles of Confederation. The objects of the Union among the States, as described in article third, are "their common defense, security of their liberties, and mutual and general welfare." The terms of article eighth are still more identical: "All charges of war and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense or general welfare, and allowed by the United States in Congress, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury," etc. A similar language again occurs in article ninth. Construe either of these articles by the rules which would justify the construction put on the new Constitution, and they vest in the existing Congress a power to legislate in all cases whatsoever. But what would have been thought of that assembly, if, attaching themselves to these general expressions, and disregarding the specifications which ascertain and limit their import, they had exercised an unlimited power of providing for the common defense and general welfare? I appeal to the objectors themselves, whether they would in that case have employed the same reasoning in justification of Congress as they now make use of against the convention. How difficult it is for error to escape its own condemnation!

Even in the final paper, Federalist No. 85 by Hamilton, addressing some of the final concerns of the Anti-Federalist that had yet to be addressed, never refereed to General Welfare, nor to Article I Section 8 in the entire paper. The single biggest concern for the Anti-Federalist was in the forming of a Federal Government that carried too much power, and the Federalist wished to relieve these concern. But in the end, so little was thought of the term general welfare as a potential or real threat of abuse of power that it warranted only a couple of paragraphs of explaining, in only one paper, never to be directly mentioned again, over the entire series of 85 writings over nearly a one year period. to quell the publics concerns and explain the new Constitution, and was sufficient to cause New York to carry ratification by a narrow 30-27 margin.

The States Debates during Ratification

PENNSYLVANIA

Even though Delaware was the first to ratify, they were not the first to seat a Convention. Pennsylvania seated their Convention on November 20, 1787, but as Delaware quickly ratified the Constitution Pennsylvania tirelessly debated it, and general welfare was not immune to the debates, and the opening volley was not small on November 28, 1787.

-

Mr. President, and it is reasoned upon as a fact, that the Congress will enjoy over the thirteen states, an uncontrolled power of legislation in all cases whatsoever; and it is repeated, again and again, in one common phrase, that the future governors may do what they please with the purses of the people, for there is neither restriction nor reservation in the Constitution which they will be appointed to administer. Sir, there is not a power given in the Article before us that is not in its expression, clear, plain, and accurate, and in its nature proper and absolutely necessary to the great objects of the Union. To support this assertion, permit me to recapitulate the contents of the Article immediately before First, then, it is declared that "the Congress shall have power to lay, and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States." Thus, sir, as it is not the object of this government merely to make laws for correcting wicked and unruly men, but to protect the citizens of an extensive empire from exterior force and injury, it was necessary that powers should be given adequate to the discharge of so important a duty. But the gentlemen exclaim that here lies the source of excessive taxation, and that the people will be plundered and oppressed.

-

To whose judgment, indeed, could be so properly referred the determination of what is necessary to accomplish those important objects, as the judgment of a Congress elected, either directly or indirectly, by all the citizens of the United States? For if the people discharge their duty to themselves, the persons that compose that body will be the wisest and best men amongst us; the wisest to discover the means of common defense and general welfare , and the best to carry those means into execution without guile, injustice, or oppression. But is it not remarkable, Mr. President, that the power of raising money which is thought dangerous in the proposed system is, in fact, possessed by the present Congress, though a single house without checks and without responsibility.

-

It will be said, perhaps, that the treasure, thus accumulated, is raised and appropriated for the general welfare and the common defense of the states; but may not this pretext be easily perverted to other purposes since those very men who raise and appropriate the taxes are the only judges of what shall be deemed the general welfare and common defense of the national government? If then, Mr. President, they have unlimited power to drain the wealth of the people in every channel

-

(December 4th),Certainly Congress should possess the power of raising revenue from their constituents,for the purpose mentioned in the eighth section of the first Article, that is "to pay the debts and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States."

But also addressed was the lack of power the Articles of Confederation gave the Congress, and that the new Constitution did need to give the government internal powers as well, specifically in regards to taxation.(December 11, 1787)

-

I know that Congress, under the present Articles of Confederation, possess no internal power, and we see the consequences; they can recommend; they can go further, they can make requisitions, but there they must stop,….. But certainly it would have been very unwise in the late Convention to have omitted the addition of the other powers; and I think it would be very unwise in this Convention, to refuse to adopt this Constitution, because it grants Congress power to lay and collect taxes for the purpose of providing for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.

However on December 18, 1787 the minority from the Pennsylvania publishes its “Dissent of the Minority from the Pennsylvania Convention”, detailing their objections to the Constitution (as seen in Part 6)

NEW JERSEY

On December 11, 1787 the Ratification Convention convened in New Jersey. Convention records do not indicate any significant debate concerning general welfare in New Jersey. n December 18, 1787 New Jersey became the 3rd State to ratify the Constitution by a unanimous vote.

GEORGIA

December 25, 1787 Christmas Day, the Georgia Convention seats. As with Delaware and New Jersey before her, nor significant debate about general welfare is found in the records. On January 2, 1788 Georgia became the 4th State to Ratify the Constitution.

CONNECTICUT

-

This is a most important clause in the Constitution; and the gentlemen do well to offer all the objections which they have against it. Through the whole of this debate, I have attended to the objections which have been made against this clause; and I think them all to be unfounded. The clause is general; it gives the general legislature "power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises to pay the debts, and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States."

Ellsworth went on the list three specific objection.

-

It was too extensive

-

It was partial

-

Congress ought not possess the power to tax at all

In his first objection he described that it gave the congress the power to place a tax on anything. But his arguments were only limited to the topic of taxation, and not to a general power. As with other arguments about excessive taxation and corruption and oppression, he also argued that the taxes of Connecticut should not go to the citizens of New York. He also insisted that Congress should not be able to tax since since it also had the power to declare war, or to keep the purse and the sword in the same house, this is the making of a despot government.

Despite Oliver Ellsworth’s objections, Connecticut became the 5th State to ratify the Constitution on January 8, 1788 by a 128-40 vote.

MASSACHUSETTS

Massachusetts convened its Convention on January 9, 1788 the day after Connecticut became the 5th State to ratify the Constitution. Massachusetts would become the first State to also propose Amendments or other changes to the Constitution in part with its ratification.

January 17th was the first time Article I Section 8 Clause 1 would be addressed, but it was in reference that taxes would be collected would be apportioned according to the population of the States. The concern was that this was a flawed measure, since early census’ counts were far from perfect.

On January 21, Mr. Dawes made this observation about the clause

-

The reason of giving this power is to render the sword unnecessary for without this power Congress cannot compel a State to pay without an army—perhaps Congress may never have the necessity as they now have imposts and excises. But Congress will not raise direct taxes but for necessity.

-

Objects to direct taxation. Congress should have some powers, but,it is difficult to draw the line, but it ought to be drawn between the sovereignty general government and of each State. Now the sovereignty of this State is given up, as the general government may prevent our collecting any taxes. Now if the power had been conditional, if a State refused, he should have no objection. Now Congress may prevent each State from supporting its own government.

Mr. Singletary followed this with:

-

The power is unlimited in Congress—he objects against it—a new case—as much power as was ever given to a despotic prince—will destroy all power in this of raising taxes, and we have nothing left—the only security is, we may have an honest man, but we may not have—we may have an atheist, pagan, Mahommedan— must take care of posterity—few nations enjoy the liberty of Englishmen. Is for giving up some power but not every thing—no bill of rights—civil and sacred privileges will all go.

This would be a prelude to Massachusetts proposing a variety of Amendments to the Constitution.

On January 22nd as debated moved forward, this concept of too much power granted to the Federal Government and a need in restricting powers was expressed

-

These words, sir, I confess are an ornament to the page. And very musical words—But they are too general to be understood as any kind of limitations of the power of Congress, and not very easy to be understood at all. When Congress have the purse, they are not confined to rigid economy, and the word debts here is not confined to debts already contracted, or indeed, if it were, the term "general welfare" might be applied to any expenditure whatever.

Debate on general welfare transpired for other parts of the Convention in the same manner as seen in other states. On January 31, 1788 the Convention agreed to the Constitution, but with the request of Amendments. After some revising Massachusetts finally became the 6th State to ratify the Constitution, with the following provision.

-

And as it is the opinion of this Convention that certain amendments & alterations in the said Constitution would remove the fears & quiet the apprehensions of many of the good people of this Commonwealth & more effectually guard against an undue administration of the Federal Government, The Convention do therefore recommend that the following alterations & provisions be introduced into the said Constitution.

The very first amendment proposed was this to help quell the apprehension of many over an excess of power to the Congress, which included General Welfare.

-

First, That it be explicitly declared that all Powers not expressly delegated by the aforesaid Constitution are reserved to the several States to be by them exercised.